The most famous storyteller of São Paulo and one of those who most often mentioned the city in his songs, Adoniran Barbosa immortalized its characters and the changes that the metropolis went through during the period of its modernization, in what journalist Eduardo Martins called, in 1980, in the Estado de S. Paulo, the musical listing of a city whose symbols remain only in memory. No one in music has portrayed the capital of São Paulo, as he did, in such an affective way, as it moved towards the place that would be called the “locomotive of Brazil” at an eye-popping speed.

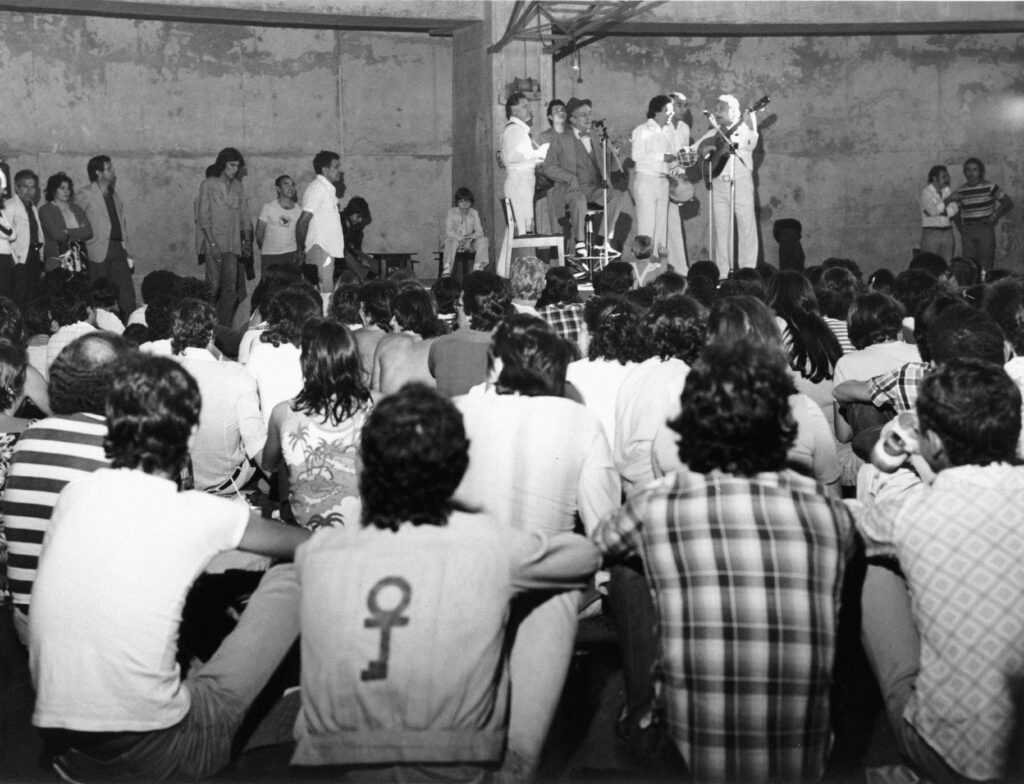

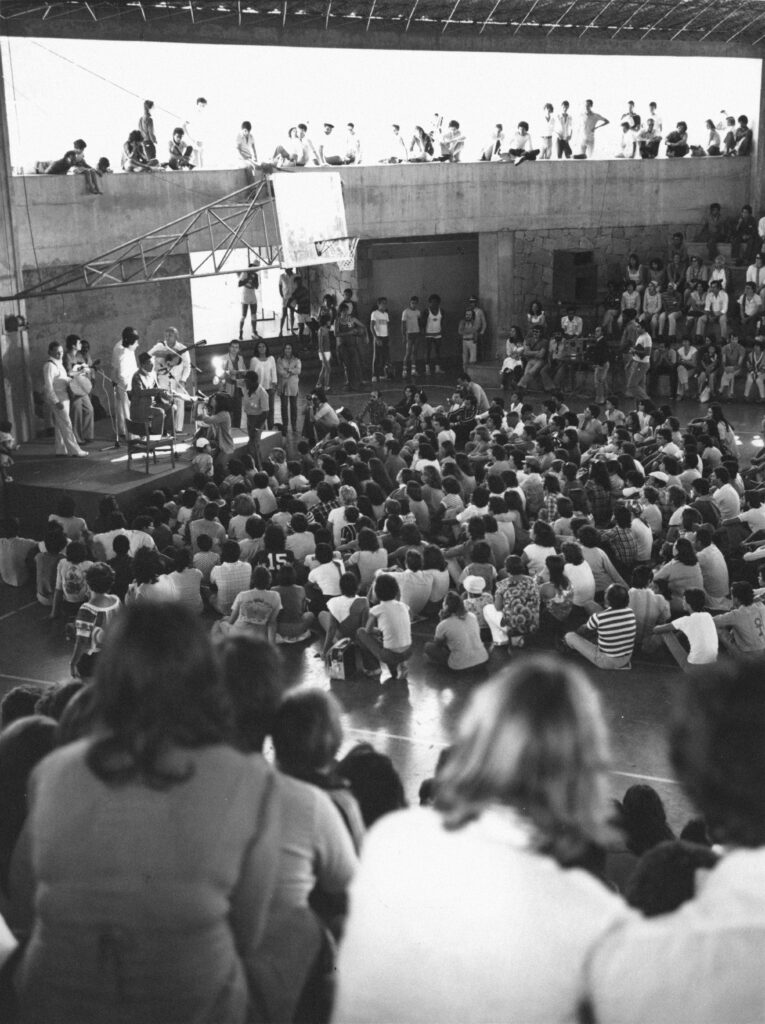

On the album Relicário: Adoniran Barbosa (ao vivo no Sesc 1980), the new and fourth release from Sesc’s Relicário project, some of his most emblematic songs help tell the story of the passage of time in São Paulo. On the stage of the Teatro Pixinguinha, which used to be at the Sesc Consolação, accompanied by the Talismã ensemble, over the course of eleven tracks he reminisces nostalgically about the past, criticizes so-called progress and mentions typical São Paulo characters, usually with a lot of humor, an easy task for the former comedian who became known for the character Charutinho.

The master tape was donated by Max Boschi to Sesc Memórias – created in 2006 to gather, systematize and make available the documentation produced and/or accumulated by Sesc – when he was invited to take part in the Oral History project, which gathers accounts from employees and former employees who worked in programs linked to Sesc São Paulo. Boschi joined the institution as a social counselor in the Mobile Social Guidance Units. Unimos, as they were called, were large Veraneio cars that, between 1965 and 1976, drove around various cities in the state with teams of social counselors who carried out activities in places where there were no Sesc social and cultural facilities. He worked at the Campinas, São Carlos, Araraquara and Bertioga units, as well as Consolação, Pompeia and the administrative headquarters of Sesc São Paulo, all three in the capital. One of his most outstanding roles was as coordinator of Instrumental Sesc Brasil, during the project’s first eight years.

In that year of 1980, Adoniran Barbosa, São Paulo’s most prominent samba singer, celebrated his 70th birthday, with a day of festivities that began with a mass at Nossa Senhora Achiropita Church, the patron saint of Bixiga, and ended with a concert in a square in the neighborhood, an Italian stronghold in the city – which the son of immigrants João Rubinato, his real name, frequented a lot. He also released the album “Adoniran Barbosa” (also known as “Adoniran Barbosa e Convidados”), only the third in his almost fifty-year career, with the participation of names such as Clara Nunes, Djavan, Elis Regina, Gonzaguinha, Clementina de Jesus, Carlinhos Vergueiro, MPB 4 and Roberto Ribeiro, unequivocal proof of his prestige.

The performance at Sesc Consolação began with the fun “Já Fui Uma Brasa” (his composition with Marcos César), a reference to the youthful expression “é uma brasa[1]“, popular among young artists at the time the song was released on the artist’s first album, “Adoniran Barbosa” (1974). “Hoje o rádio que toca iê-iê-iê / tocava ‘Saudosa Maloca’[2]“, says a passage. In the middle of the song, he makes a joke: “Eu ia passando, o broto olhou pra mim e disse: ‘É uma cinza, mora?’“[3], he says, drawing laughter from the audience. “Enganei o broto, porque, debaixo da cinza, se assoprar, tem muita lenha pra queimar“[4], he adds, earning applause.

In a good mood, Adoniran tells the audience to say “you’re welcome” after he says “thank you very much”. He asks: “Give me my mel, please, my mel[5]“, referring to his drink, and is applauded again. Then it’s the turn of “As Mariposas” (the moths), his own composition, in which he compares the insects flying around the “lâmpidas[6]” with women around him. The scene was seen by the artist in an abandoned mansion and inspired the joke.

In an interview with Estado de S. Paulo on March 10, 1979, the singer-songwriter talked about the mispronunciation of certain words, a hallmark of his creations. “In my songs, I want to speak to the people, the way the people speak. People do speak wrong, ‘nós fumu’, ‘nós cheguemo’[7]. You can’t say, for example, ‘vamos conosco’[8]. Well, ‘vamos conosco’ doesn’t work, he points out.

The next song is the classic “Samba do Arnesto” (in partnership with Alocin), which was censored by the dictatorship and couldn’t be released on the artist’s first album, in 1974, and was only released for his second album, in 1975. The justification? It wasn’t acceptable to “use bad language in the media”. Recorded in 1955 by Adoniran himself on a 78 RPM record, it had little success, even though he was at the height of his career as a comedian. The track only became a hit with the group Demônios da Garoa in 1957. According to guitarist Ernesto Paulelli, his friend had written it for him.

“Um Samba no Bexiga”, which deals with Adoniran’s origins and his relationship with the neighborhood, is full of references: “Domingo nós fumo num samba no Bixiga / Na Rua Major, na casa do Nicola / À mezza notte o’clock / Saiu uma baita uma briga / Era só pizza que avuava / Junto com as brachola”[9]. “I find it funny when people ask me when I write my songs. There’s no secret. You just have to observe the world that’s there and it comes out of you,” the artist told the newspaper O Estado de S. Paulo in 1979.

In “Iracema”, about his beloved who was run over in the middle of Avenida São João, he denounces the dangers that the major changes in traffic have brought: “Iracema, eu sempre dizia / Cuidado ao travessar essas ruas / Eu falava, mas você não me escutava, não / Iracema, você travessou contramão”[10], the lyrics announce. It is said that actress Nair Belo disapproved of the idea of the song: “Adoniran, are you crazy? What is this, a samba about a woman being run over? Nobody will like something like that. You can be sure of that,” he said. The track, however, would be recorded by him with Elis Regina, in a 1978 TV special, and with Clara Nunes, on the 1980 album.

Even the romantic “Uma Simples Margarida” is marked by the observation of the advance of progress in the city. “Eu menti pra conquistar seu bem-querer / Eu disse a ela que trabalhava de engenheiro / Que o metrô de São Paulo estava em minhas mãos”[11], he says. Good mood is also present in the marchinha “Senta Senta”, with minimalist lyrics. “Viaduto Santa Efigênia”, on the other hand, is an ode to this architectural landmark in São Paulo. “Saudosa Maloca”, which follows, is inspired by a true story that shows the process of gentrification of some neighborhoods in the metropolis, talking about a house that gave way to a tall building – the maloca mentioned in the lyrics, according to Adoniran, was actually the ruins of a hotel on Rua Aurora, in República, where Joca and Mato Grosso, the song’s characters, lived.

In response to requests for “one more song”, he returns for the encore, the 11th track, his best-known song, “Trem das Onze”. With it, he managed to break a taboo for being from São Paulo and win a carnival contest promoted by Rio’s city administration in 1965, in celebration of the city’s 400th anniversary. He did indeed take a train at one point in his life, but Jaçanã only made it into the lyrics because it rhymed with “de manhã” (in the morning), since Adoniran’s destination was Santo André, in the ABC Paulista. And he wasn’t an only child: the one who came home early to keep his mother company was his younger brother.

The record is an emblematic compendium of songs by the son of Italian immigrants who managed to capture the spirit of São Paulo and its people like no one else. The city portrayed in his songs was the one that remained invisible when the metropolis entered the modernization process, with the workers as characters, the ordinary people who helped build the locomotive, but never had the proper visibility in this process. Combining good humor and melancholy, Adoniran Barbosa masterfully describes a city that was disappearing before his eyes.

“Until the 1960s, São Paulo still existed. Then I looked, but I couldn’t find São Paulo. Brás, where’s Brás? Bexiga, where’s Bexiga? Apart from the streets of 13 de Maio, Fortaleza and Rui Barbosa, Bexiga no longer exists. They told me to find Sé, but I didn’t”, he said, in a quote published by Estado de S. Paulo in 1982. That city, however, can still be found in his songs today.

[1] Literally translated as “it is hot coal”, it is an expression extensively used by the young people during the 1960’s to refer to a cool thing or person, as well as to a physically attractive person.

[2] “Today the radio that plays yeah, yeah, yeah / used to play ‘Saudosa Maloca’” (“iê-iê-iê” refers to Brazilian rock and roll during the 1960’s, due to expression yeah, yeah, yeah, present in some Beatles songs, such as She Loves You, for example. It is a way to phonetically refer to expression in English.)

[3] “I was passing by, the babe looked at me and said: ‘It’s ashes, you dig it?'” (here there is a pun between the words “brasa” – hot coal; and “cinza” – ashes; meaning that the lyrical subject is not so attractive anymore.)

[4] “I fooled the babe, because under the ashes, if you blow on it, there’s a lot of wood to burn”

[5] In some contexts, in Portuguese, “mel” (honey) means cachaça or any alcoholic beverage.

[6] A way in which some regions of the interior of São Paulo and some parts of the capital refer to the word “lâmpada” (light bulb), typical Italian immigrant speech at the time.

[7] A very informal and regional way to say, “we went”, widely used in some regions of the interior of São Paulo and some parts of the capital.

[8] In opposition to the prior expression, it is a very formal way to say the same thing.

[9] “On Sunday we went to a samba in Bixiga / In Rua Major, at Nicola’s house / At midnight / There was a huge fight / There were pizzas flying around / Along with the braciole” (the lyrics are full of regional expressions used by Italian immigrants, such as “avuava” and “brachola”.)

[10] “Iracema, I always said / Be careful when you cross these streets / I spoke, but you didn’t listen / Iracema, you crossed the wrong way”

[11] “I lied to win her heart / I told her I worked as an engineer / That the São Paulo subway was in my hands”

Kamille Viola is a journalist and music researcher. She wrote the book “África Brasil: um dia Jorge Ben voou para toda a gente ver”, by Edições Sesc.

About Relicário: Adoniran Barbosa (Ao vivo no Sesc 1980), you may also read:

Utilizamos cookies essenciais para personalizar e aprimorar sua experiência neste site. Ao continuar navegando você concorda com estas condições, detalhadas na nossa Política de Cookies de acordo com a nossa Política de Privacidade.