In 1998, at the age of 66, João Gilberto lived isolated in his apartment in the Leblon neighborhood of Rio de Janeiro. He didn’t answer the phone or open the door, and rarely went out on the street. Demanding, he used to complain about the sound quality in his shows and got irritated with noises during his presentations. Sesc Vila Mariana had been inaugurated in December of the previous year, and the father of Bossa Nova was one of the first great names to step on the stage of its theater. Therefore, when the artist went to perform a series of shows there, between April 3rd and 5th of that year, the atmosphere was tense.

Everything went magically well, as revealed by the unreleased recording that comes to light 25 years later. Recorded on the last night of that short season, the album Relicário: João Gilberto (live at Sesc 1998) now comes to the public’s ears through Selo Sesc (Sesc Record Label), inaugurating the Relicário project, and shows a calm and good-humored João Gilberto in front of a reverent audience.

Among the treasures of the presentation is a previously unreleased song in his repertoire, which he would never record in a studio. “Rei sem coroa” [King whithout a crown] was written by Herivelto Martins from a theme he received from Waldemar Ressurreição, his partner in this and many other songs. The lyrics were inspired by the story of King Carol II of Romania, who, after being forced to abdicate his throne during World War II in 1940, went to live at the Copacabana Palace “without any blatant royalty” and soon became the talk of Rio de Janeiro.

The story inspired two songs by the duo, both performed by Francisco Alves, who, curiously, was known as the King of Voice. “Que rei sou eu?” [What king am I?] was recorded in November 1944 and released in January of the following year, becoming a big hit in Carnaval, while “Rei sem coroa” was recorded in April 1945 and released in May of the same year.

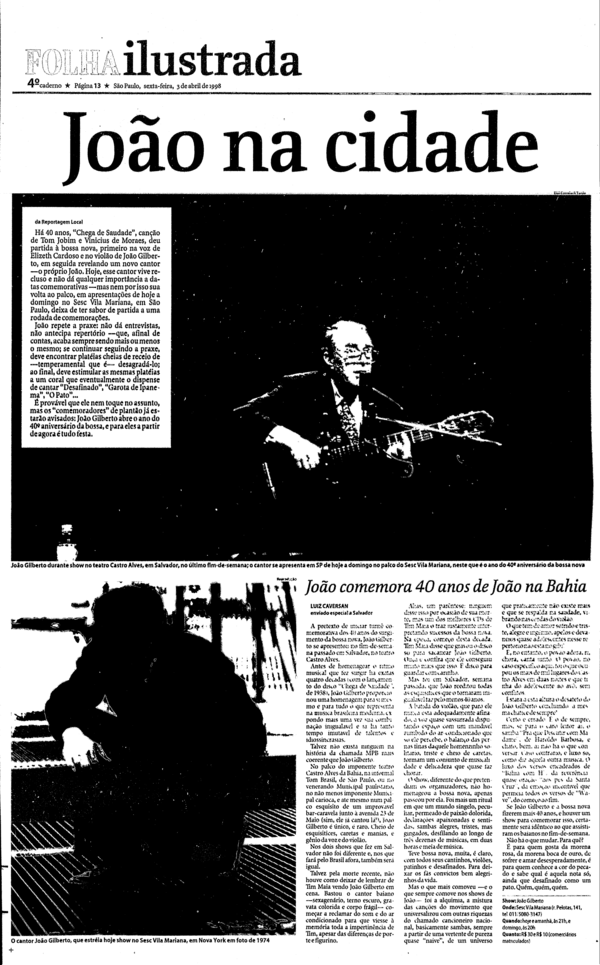

João Gilberto had opened in Salvador the tour celebrating four decades of Bossa Nova, which would also stop in São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Brasília, Recife and Maceió. The commemorative milestone was the release, in August 1958, of a 78-rpm compact containing on one side “Chega de saudade” (a classic by Tom and Vinicius that had been released in April of that year in the voice of Elizeth Cardoso, on the record Canção do amor demais, with the participation of João and his different beat on the guitar) and on the other side “Bim bom” (one of the rare compositions by the Bahian). He had only four requests to the organizers: a piano bench, a Persian carpet, a table for the guitar and perfect acoustics – this last item the greatest challenge.

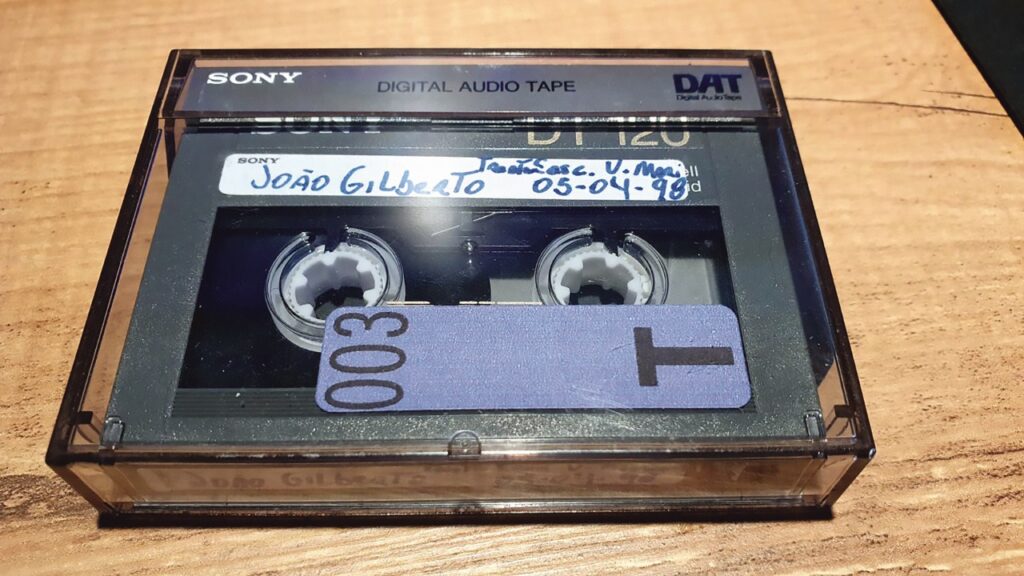

The record of the show at Sesc Vila Mariana remained untouched for 20 years. Until, in 2018, Sesc started moving to release the album. João Zilio, responsible for the unit’s studio in 1998 and now coordinator of the audiovisual collection at Sesc, was in charge of the mission to retrieve the original recordings. But he didn’t realize that, in the box of tapes he delivered to the company responsible for mastering, the tape of João Gilberto’s concert was missing. He returned several times to the old studio in search of the master, but found nothing. Then he remembered that he had made a copy of the tape so that he could listen to it in a more practical way, but it contained a serious problem: in order for the recording to fit on the 74 minutes of a CD, he had made abrupt cuts, eliminating the clapping and the reverberation of the last note of each song. He sought out a topnotch mastering professional to insert clapping noise and make the sound closer to the original, but no matter how well done, the effect sounded unnatural.

Even so, Zilio was still not satisfied: he himself had kept the tape with the others. How could it have vanished? Once again he went back to Sesc Vila Mariana. He started searching through the studio, until he found a box of cassette tapes that had been separated for filing and when he opened it, he finally found the master of João Gilberto’s show. Thus was born the recording that comes to light in the Relicário project. The same one that João Zilio himself had filled in with the artist’s name and the date of the show 20 years before.

The album tried to be as faithful as possible to what happened that Sunday at the Sesc Vila Mariana theater, capturing the atmosphere of the performance. The silences and even the coughs of the spectators were preserved. For almost two hours, João sings about love and unlove, the homesickness for Bahia, and samba itself. In absolute respect and reverence, the audience seems to listen carefully to each note. Without saying a single word, the singer is applauded at the end of each song.

Around the tenth track, a moment of tension. “I am finding the guitar strings hard, is it something there, air, fire?” he says, after singing “Louco”, by Henrique de Almeida and Wilson Baptista. Everyone seems to hold their breath, but he quickly changes to the next song, “Pra que discutir com madame”. Further on, another of the rare instances in which João speaks, at the end of “Corcovado”: “Octavinho, come here, please. Excuse me, sorry.” This is music producer Octavio Terceiro, his faithful squire for 40 years, who died in October 2020. “Great Octavio,” says the artist, drawing laughter from the audience, who seem relieved with the calm atmosphere of the show.

Out of the 36 tracks, only one was written by him, the instrumental “Um abraço no Bonfá”. As was customary throughout his career, João Gilberto mixed mostly old sambas and Bossa Nova classics. The most impressive thing about the artist’s vast repertoire of sambas from the 1940s and 1950s was that he reportedly didn’t collect records – and at that time there was no internet. He would bring these songs from memory, play them for himself exhaustively, creating new harmonies, polishing them until he considered them ready, to finally present them, completely transformed, in his shows. And he kept on modifying them, that is why one of his presentations was never the same as another.

The recipe was being deciphered over decades by his followers: slowing down the samba, he reproduced the tamborim beat with three fingers of his right hand on the guitar, and the surdo beat with his thumb. The cadence repeats itself, in a circular form, and the rhythmic division is precise: sometimes he sings ahead of the guitar, sometimes behind. In João Gilberto, voice and guitar have the same volume and merge, becoming a single body.

The album starts with “Violão amigo”, by Armando Marçal and Bide, from whom he also sings “A primeira vez”. From Caymmi, one of the composers most recorded by him, João Gilberto selected “Doralice” (with Antonio Almeida), “Rosa Morena” and “Saudade da Bahia”. “Isto aqui o que é?” by Ary Barroso, another of João’s favorites, and the choro “Carinhoso” (Pixinguinha and João de Barro) are also present. And he also interprets three songs recorded by Orlando Silva, the singer he most admired: “Curare” (Bororó), “Aos pés da cruz” and “Preconceito” (the last two by Zé da Zilda and Marino Pinto).

From Bossa Nova – a label he denied, claiming to be a samba artist –, João Gilberto evokes many hits on the record, most of them by Tom Jobim, another of his favorite authors, giving the public what one would expect from a commemorative tour, after all. “My work has always been with Brazilian music. With samba, our infinite music. That which people call Bossa Nova and that I call samba, Brazilian music – wide, rich, infinite, on which the artist can create his personal phrasing,” he told O Globo newspaper in a rare interview in 1979.

“Corcovado” and “Wave” (by Tom Jobim), “Retrato em branco e preto” (by Tom and Chico Buarque), “O pato” (Jayme Silva and Neuza Teixeira), “Chega de saudade” (Tom and Vinicius), “Desafinado”, “Samba de uma nota só” and “Caminhos cruzados” (the three by Tom and Newton Mendonça) are some of the songs from the movement that João helped found in the repertoire.

In “Chega de saudade”, the singer gives the cue for the audience to interpret the song, stopping singing, but continuing to play. Gently, little by little, the audience joins in the fun. At the end, he is nice: “I love this choir, heh, I like it (laughs). Sometimes I want to ask, but I get embarrassed,” he guarantees, to general laughter. The atmosphere is so good that the fans take the risk of shouting for songs – one of them would be answered later, when he intones “Wave”, the penultimate song of the recording (“Do you know ‘Wave’?”, provokes João). He again encourages the choir in “Eu sei que vou te amar”, and is once again answered. The album ends with the Jobim-esque “Este seu olhar”, followed by an ovation.

Long awaited by the artist’s fans, the recording shows João Gilberto at ease, as rarely seen in his performances in Brazil. Not surprisingly, for many, the shows at Sesc Vila Mariana are among the singer’s best of that period. Far away from the comings and goings of waiters, noises of glasses and cutlery, in a theater with good acoustics and quality sound equipment, he performs the songs with meticulous precision. For almost two hours, he does what he does best: reinvent Brazilian music.

The album cover brings a graffiti made by the visual artist Speto, an important name in urban art, in honor of João Gilberto. The work was registered in 2020 on the gable of a building on Avenida Senador Queirós, in the Santa Ifigênia neighborhood, near the Mercado Municipal, in São Paulo – Brazil. Speto, who is a fan of the musician, says that the idea came up in 2019 after João Gilberto’s passing, which left him very moved, as well as upset because the federal government did not pay a single tribute to one of the greatest artists Brazil ever had.

Through mutual friends, he reached out to Bebel Gilberto, João’s daughter, and very kindly proposed the tribute, since the loss was recent. She loved the idea and said she was a fan of his work. With the approval, another phase began: he needed the money to carry out the project, since the cost of painting a building is high, even without any profit. For months he persisted in his efforts, until the São Paulo Culture Department was made aware of his proposal and committed to making it work.

Speto explains that he made the image using as few strokes as possible, in allusion to the minimalism of Bossa Nova and, above all, João Gilberto. The artist is sitting, floating, in Rio de Janeiro, the city where he lived. And he is muffling his guitar, as someone who has just played a song does, in allusion to the end of an act, to life coming to an end.

Kamille Viola is a journalist and music researcher. She wrote the book “África Brasil: um dia Jorge Ben voou para toda a gente ver”, by Edições Sesc.

About Relicário: João Gilberto (Ao vivo no Sesc 1998), you may also read:

Utilizamos cookies essenciais para personalizar e aprimorar sua experiência neste site. Ao continuar navegando você concorda com estas condições, detalhadas na nossa Política de Cookies de acordo com a nossa Política de Privacidade.